Author Rob Neyer On Protective Gear For MLB Pitchers in New Book “Power Ball”

Former ESPN columnist and sabermetrics guru Rob Neyer takes a unique look into today’s game of baseball with his new book, “Power Ball: Anatomy of a Modern Baseball Game.” The chapters are divided into every half inning as he viewed a game between the Astros versus the Athletics on September 8th, 2017. Neyer dives into numerous topics including the role of sabermetrics, strategies, spin rates and overall changes not just over the past few decades but since the “Moneyball” A’s in the early 2000’s.

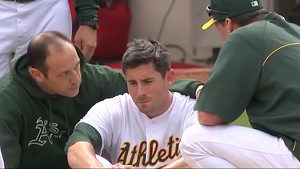

In the top half of the third inning, Carlos Correa lines a shot up the middle that deflects off the mound and hits the thigh of A’s starting pitcher Jharel Cotton. The exit velocity was calculated at 109.7 MPH off the bat. This turned out to be Cotton’s second close call of the day, the first being in closer proximity to his head. Neyer then goes into the evolution of head protection at the big league level and the role of MLB over the past few years. Here are a few excerpts from the “Visitors Third” by Rob Neyer.

In the wake of McCarthy’s near-death experience, there were serious efforts by various companies to create something major leaguers would actually, you know, wear. And before the 2014 season, MLB approved a product from isoBLOX that essentially was a cap with plastic and foam inserts. Aside from looking odd-which matters quite a lot to most of the pitchers-there were other issues, particularly the weight; the isoBLOX caps weighed roughly three times as much as the standard caps. Granted, we’re only talking about ten or eleven ounces. But that’s actually a lot of ounces when it’s on your head. There was also a breathability issue. McCarthy tested one, but found the headgear both “too big” and “too hot.”

That June, though, San Diego Padres relief pitcher Alex Torres donned the isoBLOX cap and wore it the rest of the season.

He was the only one.

Another “prospect” arrived before the 2016 season. In spring training, twenty pitchers were slated to receive a visor/helmet hybrid from a manufacturer called Boombang; to avoid the dreaded visor look, the helmets were designed to be worn over a skullcap, so from a distance the whole contraption would resemble a slimmed-down batting helmet.

Alas, what Boombang called the Half Cap reportedly weighed ten to twelve ounces, and it still didn’t look the way major leaguers want to look. And with Alex Torres getting released near the end of spring training, not a single pitcher used anything so obvious during that season. Or in this one either.

Neyer goes on to discuss Mike Coolbaugh, a minor league base coach that was killed after being struck in the neck by a line drive. In the aftermath, MLB mandated that all base coaches, major league and minor league, wear helmets.

You can almost bet that if a professional pitcher were killed in the line of duty, MLB would push hard for something, eyewash or not, and the union would be ill-equipped to resist. That said, MLB could mandate, right now, protective gear for pitchers in the minor leagues, and has not. At the very least, Baseball could push harder for more major-league pitchers and perhaps all minor leaguers to experiment with the products out there now.

When Brandon McCarthy was struck, then A’s reliever Sean Doolittle was in the clubhouse, he told me, “because the night before I’d taken a liner off my shin. I knew that could have been me, and it made me realize how vulnerable we are.”

So does Doolittle wear anything now? Nope. “I think I’m where a lot of guys are,” he says. “You try something and say, ‘I wanna wear something, but this isn’t it.’ The tech has to be there, lighter weight.”

What makes this inaction all the stranger? There actually is a piece of equipment that’s both light and reasonably protective, and Collin McHugh’s wearing it tonight.

Not that you’d ever know. McHugh’s SST Pro X Performance Head Guard, a thin pad constructed of carbon fiber, weighs just 1.7 ounces and slips easily between the body of McHugh’s cap and the interior headband. McHugh’s been using the SST since 2014, when the product’s inventor-not coincidentally, a high school friend of McHugh’s-introducted it to him.

“I was skeptical,” McHugh says, “because I had seen the other things they’d done, the isoBLOX. But I said sure, I’ll try it out. I looked at it, gave it a couple of runs in bullpens, and it just made too much sense. It was like, if I can wear this without feeling uncomfortable, and it gives me an extra later of protection, why not? So I’ll probably never throw another pitch without it.”

That was two years ago. So is McHugh surprised that he’s still one of just a dozen or so pitchers using SST? “Extremely surprised,” he says. “They’ve come up with the other products, but guys aren’t going to wear them; too blocky, they’re big, they’re uncomfortable, they’re gimmicky. Baseball players, and pitchers in particular, are pretty obsessive about their comfort level, about the way they feel on the mound. But for me, this is comfortable. Maybe a sleeve would help, since some guys maybe don’t want to worry about something sliding around every time they take off their hat. I don’t see it as a big impediment. But a lot of guys do.”

You talk to McHugh, and you just can’t help wondering why they’re not all using what he’s using. But there’s an awareness issue too. When I asked Jharel Cotton about adding protection, he seemed sincere about his worries. “I would wear something if they make it comfortable,” Cotton said. “It’s like wearing a cup. I do wear a cup; some pitchers don’t, but it’s comfortable so I wear one. I like my life and would do anything to protect that.” He also said he’s never even seen an SST Head Guard.

Today, almost exactly five years after Brandon McCarthy might have suffered a fatal injury on this very spot, Jharel Cotton remains entirely unprotected, just as hundreds of other pitchers in all the other stadiums-or thousands, if you want to include the minor leagues-remain unprotected. There’s nobody to blame for this really; the pitchers don’t want an additional hindrance, no matter how minor, and they also don’t want to look different, or scared. And you know, they’re young; young men with tremendous physical talents tend to think they’ll live forever.

But as the pitchers keep growing and throwing harder, and the hitters keep growing and swinging harder, there will be more concussions and fractured skulls and shattered jaws and dental disasters and ruined careers. Unless something is done. And I suppose if we do insist on blaming someone, we should blame the MLB Players Association for not doing more to create awareness; at the very least, why not send a dozen SST Head Guards to every major league clubhouse, and see what happens?

Previous Post

Previous Post